How do the number and size of potential prey affect choices made by cats?

Math — we all do it on some level (even if we don’t like to!), including other animals. For most animals, the most obvious and well-established form of numeracy is quantity discrimination, or the ability to tell a larger amount of something from a smaller amount of something. Birds do it, bees do it, fish do it, and cats do it too!

I have already blogged about two previous studies of quantity discrimination in cats, which found that cats can sort of tell the difference between two dots and three dots, and tend to choose a larger, rather than smaller, amount of food.

Now before you get too excited about the possibility of your cat doing your algebra homework, keep in mind that it might be better to assess cats’ “number sense” in a task that is more natural to them. That’s exactly what folks from two universities in Mexico did with a new study, Revisiting more or less: influence of numerosity and size on potential prey choice in the domestic cat, which was recently published in the journal Animal Cognition.

What could be more natural to cats than checking out rodents? This study used live prey to assess cat preferences, as rats and mice were expected to trigger predatory behavior and be highly motivating to the study participants.

NOTE: No rodents were harmed in this study, and they were monitored for signs of fear during all tests. Bonus, all rats and mice were adopted by university students after completion of the study!

What the scientists did…

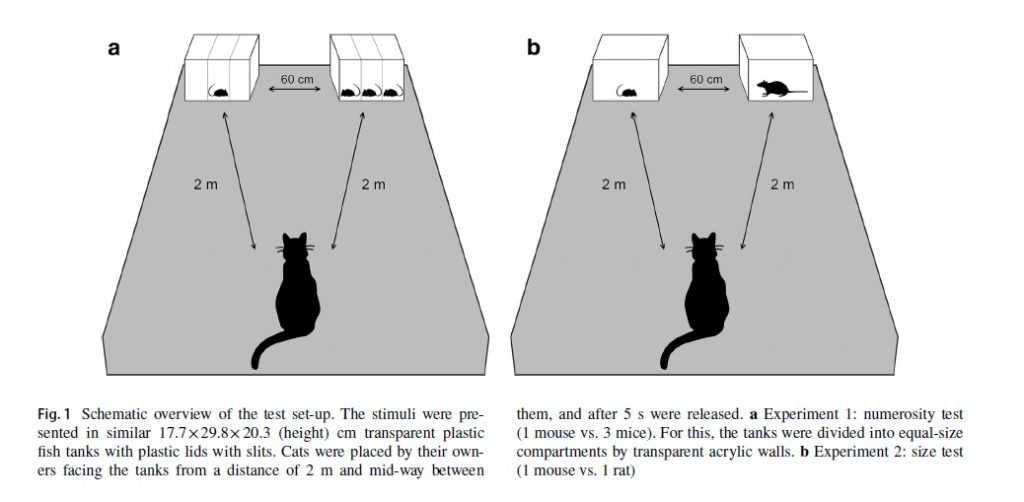

Twenty-four adult cats were tested once a week for six weeks in their homes. In the first experiment, two tanks were set up with either one or three mice within, while cats were absent. Cat owners were instructed to bring the cat into the room and place them on the floor from about 2 meters away. The cat was then released and allowed to investigate for two minutes. Next, the cat was removed from the room, and then the tanks were switched so that the right-left position of one mouse vs three mice was alternated between trials.

Experiment two was similarly designed, except this time the cat could choose between a mouse, and a larger rodent, an adult rat. Each cat was tested twice per day, for a total of six days (three days for each condition, six trials for each condition).

To assess the cats’ preferences, researchers measured how long it took the cat to approach either tank, how much time they spent near both tanks, and how much time they spent watching the rodents, during each two-minute trial. Tail swishing was also recorded for good measure, to determine excitement.

What the cats did…

So what did the cats do? First of all, five cats had to be dropped from the study due to inadequate participation, leaving data for 19 cats.

In experiment one, cats spent more time by the three-mouse tank, although 3 cats divided their time equally and 2 preferred the single mouse. Cats were equally quick to approach either tank, and there were no differences in tail swishing when watching one or three mice.

However, in experiment two, cats actually preferred spending time near the mouse’s tank, rather than hanging out by the rat. So although more might be better in this context, bigger was definitely not better as far as the cats were concerned. Why might this be?

Preferring three mice over one doesn’t necessarily mean that cats could count the number of mice in each tank. Cats may have been attracted to the additional movements of three mice compared to one: more movement = more feline excitement. Perhaps three mice mean a better chance of catching at least one!

When it come to rats and cats, bigger isn’t necessarily better. Previous research has found that cats are actually fearful of rats, and that rats can present a challenge for cats: the larger a prey animal is the less likely a cat will make a kill, and rat predation is surprisingly low among feral cats. So perhaps in this case, cats are playing it safe, knowing that should the opportunity arrive, they’ve got a better chance with the mouse. In either cases, the behavior of the cats was not simply random – they showed clear preferences! So cats can not only discriminate between quantities, they can make judgements based on the risk each choice might present!

References

Biben, M. (1979). Predation and predatory play behaviour of domestic cats. Animal Behaviour, 27, 81-94.

Chacha, J., Szenczi, P., González, D., Martínez-Byer, S., Hudson, R., & Bánszegi, O. (2020). Revisiting more or less: influence of numerosity and size on potential prey choice in the domestic cat. Animal Cognition, 1-11.

Parsons, M. H., Banks, P. B., Deutsch, M. A., & Munshi-South, J. (2018). Temporal and space-use changes by rats in response to predation by feral cats in an urban ecosystem. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 6, 146.