In the early 1900s, scientific attention to animal cognition was focused on the performance of one animal, Clever Hans the horse. His owner, a mathematics teacher, claimed that Hans could perform addition, subtraction, multiplication and work with fractions. Indeed, Hans could answer questions correctly even if his owner was not present, which led an investigative panel to conclude that this was not a case of fraud (NYTimes, 1904; Pfungst, 1911). Several months later a psychologist was able to determine that Hans could not do mathematics, but instead was sensitive to human cues of correct answers (Allen & Bekoff, 1999; Pfungst, 1911). This planted a seed of doubt in psychological explorations of the numerical abilities of non-human animals; however, these doubts have since been challenged again and again! It is clear that while non-human animals’ cognitive abilities are clearly different than those of humans, these differences, to quote Darwin, are “of degree and not of kind.”

Numeracy is the broad range of numerical applications used by humans and other animals. At its most basic level, numeracy is expressed in the ability to discriminate between the size, amount or other aspects of quantity of different objects (Devlin, 2000). Quantity discrimination has been studied in animals from fish to birds to primates, and most animals show some level of it. Many studies of numeracy have been done on carnivores, with canines overly represented. It’s time to give the kitties some scientific attention. An amount that they can detect.

“Number sense” could contribute to the survival of cats in many ways, including reproduction (how many female cats are around?), predation (how many mice are over there? how big is that rat compared to this one?), and safety (how many dogs are in that yard?). But yet only two studies of quantity discrimination have been done with cats.

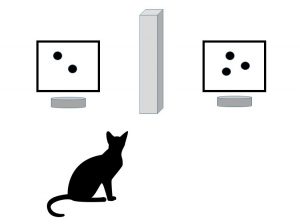

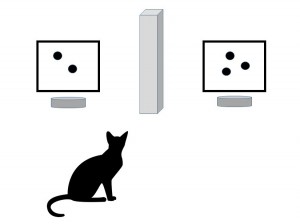

In 2009, in a study titled Quantity discrimination in felines: A preliminary investigation of the domestic cat (Felis silvestris catus), four domestic cats were tested by presenting them two food bowls with a card above them (see figure). The cards had either two or three dots printed on them. One of the two stimuli indicated a food reinforcement – for two cats the two dots indicated reinforcement, and for the other two cats, the three dots led to food. Cats were able to discriminate between the two stimuli correctly, but their performance dropped to chance when the area of the stimuli was controlled for — by increasing the size of the two dots to be equivalent to the area of the three dots on the other card.

In 2009, in a study titled Quantity discrimination in felines: A preliminary investigation of the domestic cat (Felis silvestris catus), four domestic cats were tested by presenting them two food bowls with a card above them (see figure). The cards had either two or three dots printed on them. One of the two stimuli indicated a food reinforcement – for two cats the two dots indicated reinforcement, and for the other two cats, the three dots led to food. Cats were able to discriminate between the two stimuli correctly, but their performance dropped to chance when the area of the stimuli was controlled for — by increasing the size of the two dots to be equivalent to the area of the three dots on the other card.

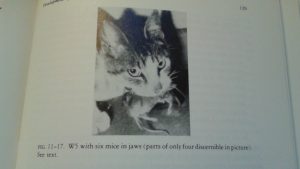

For a non-foraging, hunting species that usually catches one prey item at a time (unless you’re this cat) size discrimination may be more important than quantity discrimination.

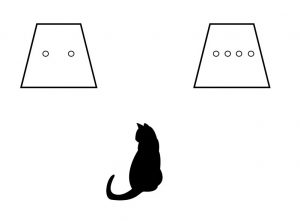

A new study (“More or less: spontaneous quantity discrimination in the domestic cat) by Bánszegi, Urrutia, Szenczi & Hudson was just added to the mix! All cats were tested in their own homes with a preferred wet food item. The cats were deprived of food for several hours before the experiment to ensure motivation. The cat was placed in between and several feet away from two white boards with the food choices hidden under a cover. When each trial began, the choices were uncovered and the cat was allowed to pick a side, and eat the food that was there (the assumption being that untrained cats would naturally prefer the side with more food, especially if they were hungry).

In the first experiment, cats were given a choice between a different number of 4-g balls of wet food. Each cat received two trials each of eight different combinations of choices – small ratios (1 vs 2 food balls, 1 vs 3 food balls, 1 vs 4 food balls, and 2 vs 5 food balls) or large ratios (2 vs 3, 2 vs 4, 3 vs 4 and 3 vs 5 food balls). Seventeen out of 22 cats chose the larger quantity more often than the smaller quantity, and performance was impacted by the ratio – with cats more likely to choose the large quantity when the difference between the two amounts was larger (in other words, it is easier for cats to discriminate between 1 vs 4 than between 2 vs 4).

In the first experiment, cats were given a choice between a different number of 4-g balls of wet food. Each cat received two trials each of eight different combinations of choices – small ratios (1 vs 2 food balls, 1 vs 3 food balls, 1 vs 4 food balls, and 2 vs 5 food balls) or large ratios (2 vs 3, 2 vs 4, 3 vs 4 and 3 vs 5 food balls). Seventeen out of 22 cats chose the larger quantity more often than the smaller quantity, and performance was impacted by the ratio – with cats more likely to choose the large quantity when the difference between the two amounts was larger (in other words, it is easier for cats to discriminate between 1 vs 4 than between 2 vs 4).

Experiment two looked at whether cats would choose a larger ball of food over a smaller ball of food. The larger food ball could be 2, 3, 4 or 5 times larger than the other ball. The answer is mostly yes. Eighteen of the 22 cats tended to choose the larger food ball more often than the smaller one, but again performance was impacted by how big the difference was between the two amounts, and when the difference was too big (1 vs 5) the cats actually tended to prefer the smaller amount.

Finally, to see if cats were using their sense of smell to make their choices, the experimenters hid food inside opaque tubes – one side had one food ball, and the other had six food balls – and let the cats “follow their noses.” Turns out the cats’ behavior was random in this condition, suggesting that cats are more likely to use visual cues over olfactory cues in the quantity discrimination task.

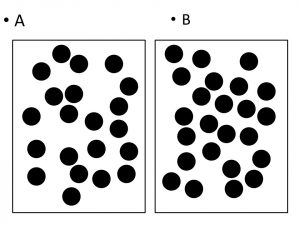

Several studies of quantity discrimination demonstrate a common influence on success: ratio. In general, in both nonhuman and human animals alike, performance on all types of quantity discrimination tasks, is best when the ratio is small, and performance degrades as the ratio approaches one. This ubiquitous effect of ratio follows a principle called Weber’s Law (Brannon, et al., 2009), which states that in order to detect a change in a stimulus, the change required is relative to the stimulus intensity, rather than an absolute amount (in other words, it’s easier to tell the difference between 5 and 10 lbs., than between 105 and 110 lbs., even though the absolute difference between them is the same).

The new study did not control for area, so when taking both studies into account, it appears more likely that cats respond to the overall volume or area as a cue more than any numerical information. So based on the results of these two studies, it seems that to cats, it is more important to find the bigger rat than to find more mice. On the other hand, if that rat is too big, it might just be safest to go for a small one – rather than risking a tangle with a very large rodent that might have very big teeth and claws.

References

Allen, C., & Bekoff, M. (1999). Species of mind: The philosophy and biology of cognitive ethology: MIT Press.

Bánszegi, O., Urrutia, A., Szenczi, P., & Hudson, R. (2016). More or less: spontaneous quantity discrimination in the domestic cat. Animal Cognition, 1-10.

Berlin’s Wonderful Horse: He Can Do Almost Everything but Talk. (1904, September 4, 1904). New York Times.

Brannon, E. M., Cantlon, J. F., Tommasi, L., Peterson, M., & Nadel, L. (2009). A comparative perspective on the origin of numerical thinking. Cognitive biology: Evolutionary and developmental perspectives on mind, brain, and behavior, 191-220.

Clever Hans Again – Expert Commission Decides that the Horse Actually Reasons. (1904, October 2, 1904). New York Times.

Darwin, C. (1982). The Descent of Man. (1871) New York: Modern Library.

Devlin, K. J. (2000). The math gene: How mathematical thinking evolved and why numbers are like gossip: Basic Books London.

Pfungst, O. (1911). Clever Hans:(the horse of Mr. Von Osten.) a contribution to experimental animal and human psychology: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Pisa, P., & Agrillo, C. (2009). Quantity discrimination in felines: A preliminary investigation of the domestic cat ( Felis silvestris catus). Journal of Ethology, 27(2), 289-293. doi: 10.1007/s10164-008-0121-0

3 thoughts on “How many mice? A new study explores numeracy in our feline friends.”