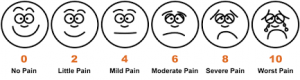

When you are in pain, how does your doctor know where it hurts? You usually have to tell them. You might draw on an image of a body exactly where you are experiencing pain, or rate your pain on a scale. Pain is typically described as an unpleasant sensation, with physical, emotional and cognitive components.

When an animal is in pain, can we tell? Maybe. For some animals, there might be clear signs of pain, such as an obvious injury. In the “old days” philosophers such as Descartes did not believe that animals felt pain, even if they had an injury; it is only in the last 30-40 years that scientists have acknowledged the likelihood that animals (particularly other vertebrates) feel pain, and that we should behave under the assumption that they do.

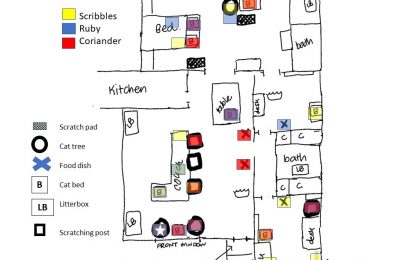

There may be some obvious indicators of pain in animals, such as refusing to put weight on a limb, or avoiding contact with a potentially pain-inducing stimulus, such as a hot stove. But there may be other less obvious indicators, such as changes in facial expression or posture, or changes in personality or appetite. With cats, pain detection can be even trickier, as we assume that as prey animals, cats are likely to hide indicators of pain and discomfort that might make them vulnerable to attack. We also know that humans often have difficulty reading their cats’ body language, including that which might suggest pain. The conclusion that follows is that cats are typically UNDERtreated for pain. So what DO we know about determining pain in cats?

Recently, two scientists, Isabella Merola and Daniel Mills, at the University of Lincoln conducted a meta-analysis/review of the last 15 years of research involving the assessment of pain in cats (“Systematic review of the behavioural assessment of pain in cats”). The goals were to assess the current tools in use and identify future areas for research. One hundred studies were reviewed, with each being assessed for method of measuring pain, whether measures were objective (behaviors) versus more subjective (inferring states, such as “the cat looks happy” or “peaceful”), and whether they assessed immediate emotional response to the pain or looked more at the cats mood or personality changes. They also assessed the validity and reliability of the tools – did they measure what they claimed to measure, and would they lead to reasonable agreement between raters?

Most of the studies were assessing cats after a surgery such as spay/neuter, or (the incredibly painful) declaw surgery, or during a repair of a fractured bone. From these studies, Merola and Mills were able to identify the types of tools used to assess pain in cats. These included scales, which might ask a rater to measure assumed pain intensity on a scale, or with specific definitions (such as lameness or response to touch). Another type of tool would provoke pain (via heat, pressure, or electricity) to see what level would lead to withdrawal by the cat. Many of these tools did not define behavioral reactions that would suggest pain aside from withdrawal responses. Scales were the most commonly used tools, but few of them reported on their validity or reliability measures (one that did: the UNESP-Botucatu scale).

Other types of tools were based more on subjective reports from the owner, behavioral observations by a researcher, or an assessment of how much a cat was inhibiting movement. Some of these tools included behaviors that would indicate both the sensory experience, and an emotional component – such as vocalizations, skin twitching, tail movements, paw shaking, sleep, and posture.

Tool use seemed to fall into two categories: use of scales for acute, provoked pain (such as surgery) which focused on the sensory experience of pain, or scales used for chronic conditions, which heavily focused on those emotional components. The process of differentiating when acute pain becomes chronic was not clear; the timescales used in the studies reviewed appeared to be inconsistent and somewhat arbitrary.

This manuscript also revealed a few important things: these tools have been assessed in very few contexts (primarily surgery and serious injuries), yet there are several conditions that may cause acute or chronic pain in cats, including arthritis, stomatitis, inflammatory bowel disease, pancreatitis, and many other illnesses or injuries.

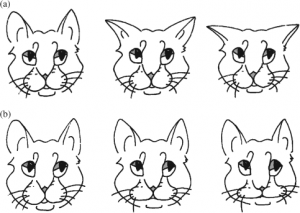

Because some of the assessments required interactions with cats that could be stressful or scary, the authors suggest that observational tools and behavioral methods are the way to go. These types of tools, with owner education, could increase the likelihood that owners would recognize and report signs of pain in their pet cats. One of the more exciting recent studies on assessing pain in cats, Evaluation of facial expression in acute pain in cats, suggests that cats in pain have statistically distinct facial expressions, with changes in both the ears and muzzle. Unfortunately, most observers had a hard time detecting these differences.

Even with the 100 studies included in this review, there are still many unanswered questions. Merola and Mills point to a few key directions for future studies, including defining acute versus chronic pain, and relying more on observation than inference. Assessment tools need to be tested in several potentially painful contexts to make sure they are universal in scope.

So back to my original question, why is pain detection so difficult in cats? I think there are a few reasons: sometimes the more you research something, the more obvious it is how little we know about that thing (in this case, how to measure feline pain). Consider that cats might hide pain, and that there have been many different tests and approaches. Let’s hope this important review helps researchers focus and unify their methods!

Thanks for this post. Since our cat was declawed before she came to us, I don’t know the intial amount of pain she suffered. But, I see her limp occassionally. Breaks my heart. We keep her on our laps as much as possible. The warmth of a cozy lap may help, but it sure can’t hurt:)

Nancy, MANY declawed cats experience painful bone regrowth in their paws (imagine having a pebble in your shoe) that can be repaired by an experienced veterinarian! It might be worth talking to your vet about.