There have been several studies of feral cat colonies, their social interactions, how cats co-exist, and what factors (such as food availability) are related to the density of cat populations (for example, a greater number of resources increases the number of cats living in a space). However, we have very little data on the other most common place domestic cats live: the human home.

The only published research related to space use in indoor cats came out in 1996, and since then, there has not been a single follow up study of feline behavior that has advanced our knowledge of how cats use space in the home! In fact there is very little research on cat relationships in the home, especially ones that aren’t survey-based. We can only hope that this glaring omission is corrected in the near future, but in the meantime, I thought it would be fun to take a closer look at this older study, and how we can apply this research and what else we know about cat behavior to assess what is going on in our own homes.

The research, “A game of cat and house: spatial patterns and behavior of 14 domestic cats (Felis catus) in the home” is in many ways what I would interpret as an anthropological study, as the authors, Penny Bernstein and Mickie Strack, made observations of the cats in one of their homes (Strack’s 14 cats). The researchers had specific questions they wanted to answer about the observed cats including:

- Do indoor cats have home ranges that can be identified? An animal’s home range is the space that they use regularly. Although sometimes confused with territory, it’s important to know the difference: territory is an area an animal will defend. Although there are vast individual differences, studies of both feral and owned cats suggest that male cats tend to have larger territories than female cats.

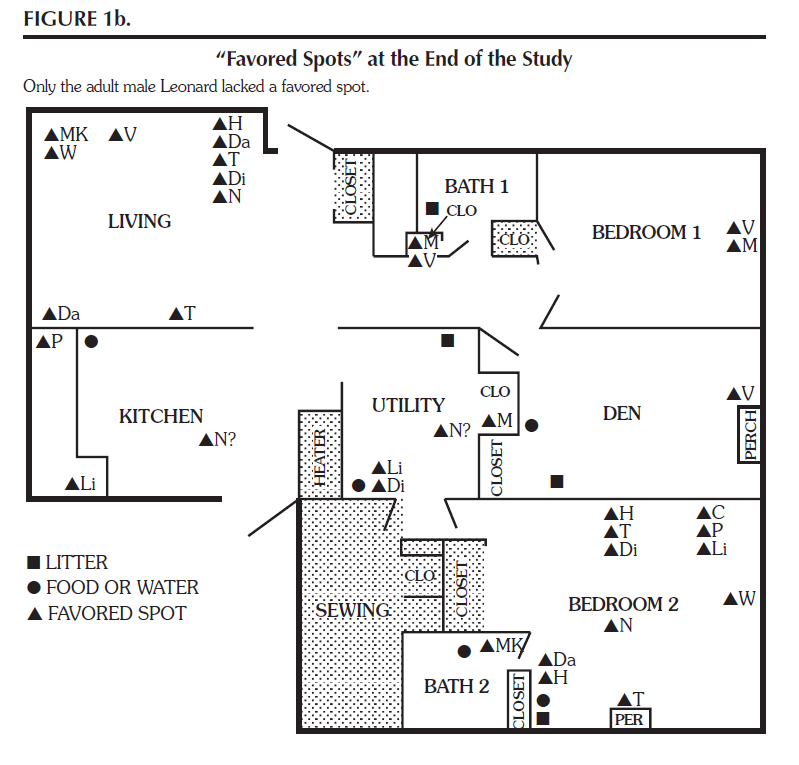

- Do individual cats have favorite spaces that they use? Could frequently or exclusively used areas be identified for the cats in the home? Would these areas be shared or only used by some cats?

- Did some cats control access to resources? Cats may prevent other individuals from using spaces in the home, either overtly or in a more subtle way. Some cats may choose to leave a spot rather than fight for it, and other cats may aggressively chase other cats away from resources.

- How does the density of indoor cats compare to that of outdoor cats? Previous studies have observed the densities of outdoor cats, but the authors were curious as to how cats in the home compared.

Research Methods

The study took place in a 1300 square foot, single story home with two humans. Strack observed the cats for approximately four hours a day, every day from January to April of 1981. At the beginning of observations, there were 14 cats in the home (7 male, 7 female) ranging in ages from 4 months to 13 years old. All cats were fed wet food once a day, with dry food and water freely available. There were two window perches and 4 litter boxes.

What did they find?

At the end of the study, the researchers could identify a home range for each individual cat, characterized by the number of rooms each cat used on a regular basis. The kittens were the only individuals that used every room in the house, and one 4-year old cat, Lily, primarily lived on tope of the refrigerator. One cat, Julius, also used most rooms of the house. After he died in the second month of observations, Lily began expanding her territory. Male cats in the study always used more rooms than female cats, suggesting that much like cats with outdoor access, there is an effect of sex on home range.

Most cats also clearly had favorite spots where they were mostly likely to be observed sleeping, resting, or grooming. All cats in the study time-shared at least one spot – meaning that the space was used by multiple cats, but NOT at the same time. Some cats also used a favorite spot together, but this was less common than time-sharing. However, those favorite spots were rarely shared by more than 3 cats. Female cats were more predictable in their use of favorite spots, with male cats being more likely to roam or be observed in different locations when observed.

Aside from some hissing and swatting, there was no overt aggression between the cats. But it did appear that some cats had “freer” access to resources than others, such as in the case of Julius, who was observed in all areas of the house. He was also observed displacing other cats from preferred spots several times a day. After Julius passed, few other cats were seen displacing others, although one cat started urine marking, and some cats began to fight as Lily’s behavior changed.

The density of cats in this study was much higher than that observed in studies of outdoor cats (113,000 cats/km2). Other research has found cat densities as low as 1 cat/km2 up to 30,000 cats/km2). However, it’s hard to directly compare these two populations because there are several things that might make it easier for cats to co-exist indoors at a higher density, including safety from predation, being neutered, and being provisioned with food and safe spaces.

The Take Home

From this study, we can see that indoor cats have distinct home ranges, and that their behavior is not independent of the cats they live with, the space available to them, or the resources that are provided. Because we keep cats at densities that are much higher than what they would naturally choose, we need to be aware of how we can make adjustments in the home to make it easier for them to co-exist! Which is exactly what I’ll discuss in my next blog post!

To be continued…

References

Bernstein, P. L., & Strack, M. (1996). A game of cat and house: spatial patterns and behavior of 14 domestic cats (Felis catus) in the home. Anthrozoös, 9(1), 25-39.

Bernstein, P. L. (2006). Behavior of single cats and groups in the home. Consultations in feline internal medicine, 675.

2 thoughts on “How do cats use space? Part 1”