I recently purchased Meowspace (for more about my Meowspace chronicles, see my past blog posts here and here) – a device that allows me to feed my cats separately, but requires the Meowspace user to learn to get in and out of a box using a microchip-controlled cat flap. Whether I trained my cat or she figured it out herself is a good question.

Even though at times I felt like she was never going to succeed at Meowspacing, it took the Nibbler less than three weeks to learn to use the cat flap. As soon as she figured it out, I lured her in, and set up a videocamera to see exactly what she was doing to get out. At first I was watching her to see what she would do once she was in the box. Turns out she was doing the same thing to me – watching me to see if I was going to help her get out.

As much of the initial training involved a lot of happy talk, doling out of treats, and even some gentle nudging or holding the flap open, I realized that the Nibbler might see me as part of this shared Meowspace experience. Humans were necessary to open the door and make this whole process of getting in and out happen. Was I hindering her learning? Or was she just dependent on me to help her solve a problem?

As you can see from the video at 0:26 and again at 1:01, 1:30 and 2:01, the Nibbler is looking at me (to her left) to come let her out. She’s making no attempts to get out on her own. But once I leave the room where she can’t see me (I went outside to go check the mail and stop myself from staring at her), she stops looking to the human (me) to help her get out and starts pushing on the door to get out on her own.

This made me think about a study from a few years back where scientists examined whether cats and dogs engaged with humans to get help solving a problem. “A Comparative Study of the Use of Visual Communicative Signals in Interactions between Dogs (Canis familiaris) and Humans and Cats (Felis catus) and Humans” asked, do cats and dogs communicate with us in the same way when they need help?

Cats and dogs are pretty different; although they are both carnivorous predators, and live with us as pets, most of the similarities end there. Perhaps most importantly, dogs have a much longer history with humans, with up to 30,000 years of domestication. Cats were more recently domesticated (estimated at 5000-10000 years ago). Furthermore, WHY they were domesticated and even HOW are very different. Dogs have been selectively bred for particular jobs, and probably even for particular behavioral responses to humans (such as facial expressions). Cats have sort of domesticated themselves – we let them into our lives because they did something we needed desperately – killed rodents – oh and they just happen to be cute and cuddly too? BONUS! Most cats choose their own sex partners, so until recently, we were not doing much selective breeding in felines for behaviors.

So back to the question: do cats and dogs differ in how they engage with humans when solving a problem? Do they emit signals to communicate with us, saying “hey, could you lend me a hand here?” Miklosi, et al. examined this question by giving cats and dogs an impossible task, and looked at what they did.

A previous study demonstrated that dogs tend to look at humans when they can’t solve a problem, in comparison to their distant relative, the wolf. Humans respond to these glances as a communicative gesture – a cry for help, so to speak, and offer assistance. So would cats expect the same help?

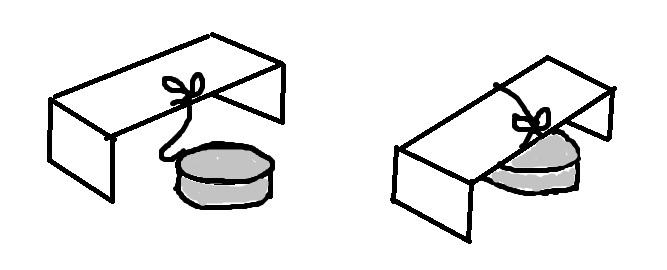

The solvable task started with a piece of food placed under one of three upside-down tubs or cans that were tied to a stool with a long string. The animal, but not the owner, was allowed to see where the food was placed. Then the subject was allowed to move the tubs to get the food. For the unsolvable task, the tub was tied so tightly underneath the stool that it could not be manipulated. The owner and the experimenter stood to either side of the animal to see if they would look in either direction.

The experimenters recorded how much time the cat or dog poked at the tub, or sat near the tub or even just looked at the tub. They also noted how long it took for the cat or dog to make a first glance at their owner or the experimenter, and how long they spent looking at a human and how many times they alternated their gaze between the two.

Results showed that both cats and dogs excelled at the solvable task. But – when the task could not be solved, differences emerged. First of all, cats spent more time touching the tub where the food was hidden. Dogs looked sooner and longer at their owners, and also alternated their gaze between the food and the humans. Most dogs looked at their human during the unsolvable task, while fewer than half of the cats did.

The conclusions? Cats do not give up easily when solving a task, and in comparison to dogs, did not look to humans to “help” them get the food when they couldn’t get it themselves. Why would this be? On the one hand, this may not be that surprising, as cats are solitary hunters, domesticated as a by-product of protecting grain and killing rodents. The domestication of dogs may have included consumption of food-scraps and human garbage. Perhaps this domestication process led to selection for a greater likelihood of interactions with humans, including eye contact. Dogs have been raised and bred to “work with” humans – in hunting, scent work, as guide dogs.

Cats have not been selected for specific jobs – in fact, there has been little behavioral selection on cats at all, aside from tolerance of humans. So one conclusion is that cats just don’t naturally look to humans as a “helper,” and that they don’t communicate with us the same way dogs do. Miklosi et al. feel that dogs are easier to train than cats (although the two studies they cite were ones that trained dogs only), possibly due to species-specific differences in gazing at humans and use of communicative signals.

This may be true. Artificial selection is powerful, and a good 25,000 additional years of dog domestication means they certainly may have a leg up on cats when it comes to interactions with humans. But I think it’s important to consider another possibility: that the potential of cats has only barely been tapped! I think that cats may be behaviorally more plastic than we give them credit for, and that most of us underestimate both their training ability and their potential to form bonds with humans.

Look at this kitty and how she looks to her human for cues:

When cats show confidence or trainability, we discredit their cat-ness by calling them “dog-like.” But perhaps the potential for cats is always there, and most cat owners just don’t bother to try training their cats! We assume “cats can’t be trained” without even trying, and by interacting with our pets less, we create a pet that interacts less with us.

I think of my own cat, and how she looked to me for help. She has been clicker trained, well-socialized and given lots of love and attention in her lifetime. She’s incredibly interactive with humans, wanting attention most of the time! I’m not sure how much of that behavior is her genes and how much of it is parenting…but regardless, it makes me think that we need to reconsider how we interact with cats before making too many assumptions about how they interact with us.