A new study compares cats who spray with those who urinate outside the litter box…

and their feline housemates.

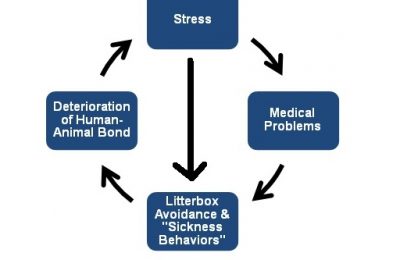

As I like to say, nothing sends cats to the pound quicker than urine around the house…whether it’s in the form of spray on the wall, or puddles on your carpet, it’s no fun for anyone. The functions of spraying are believed to be different than those of urinating, and cats who spray may continue using their litter box. However, there’s still a lot we don’t know about the motivating factors related to both behaviors, and although we can never read your cat’s mind, we can try to make some educated guesses about why they spray or urinate outside the box. We can also ask research questions that help us better understand what’s going on, which is exactly what a recently published study has attempted to do.

In “A Case-Controlled Comparison of Behavioural Arousal Levels in Urine Spraying and Latrining Cats”, researchers compared the behaviors and stress levels of otherwise healthy cats who were either spraying or urinating (“latrining” as the authors call it) in the home. They also matched each cat with a case-control – meaning a non-house soiling cat of approximately the same age and the same sex (when possible), from the same household. This study design controls for the effect of different households, because the cats will have the same environment, the key difference being that one of them is house soiling, and the other is not.

The researchers were able to match 11 spraying “dyads” – the sprayers were 2 females and 9 males, and the control cats were 6 females and 5 males. Eight of the households had at least some outdoor access. There were 12 latrining “dyads” – 10 female cats, and 2 male urinators, with 7 female and 5 male control cats. Five households had access to an enclosed yard, and the remaining cats were indoors only. All cats in the study were neutered.

To measure stress, researchers looked at cortisol levels in all of the cats’ poop (fecal cortisol metabolites). Cortisol is a hormone released by our adrenal glands that is often used to measure stress levels. Measuring cortisol from poop has been validated in previous studies and is considered a non-invasive way to detect stress (by a scientist whose last name is Schatz, I kid you not, or maybe I am just easily amused). Owners were given equipment and careful instructions on poop collection.

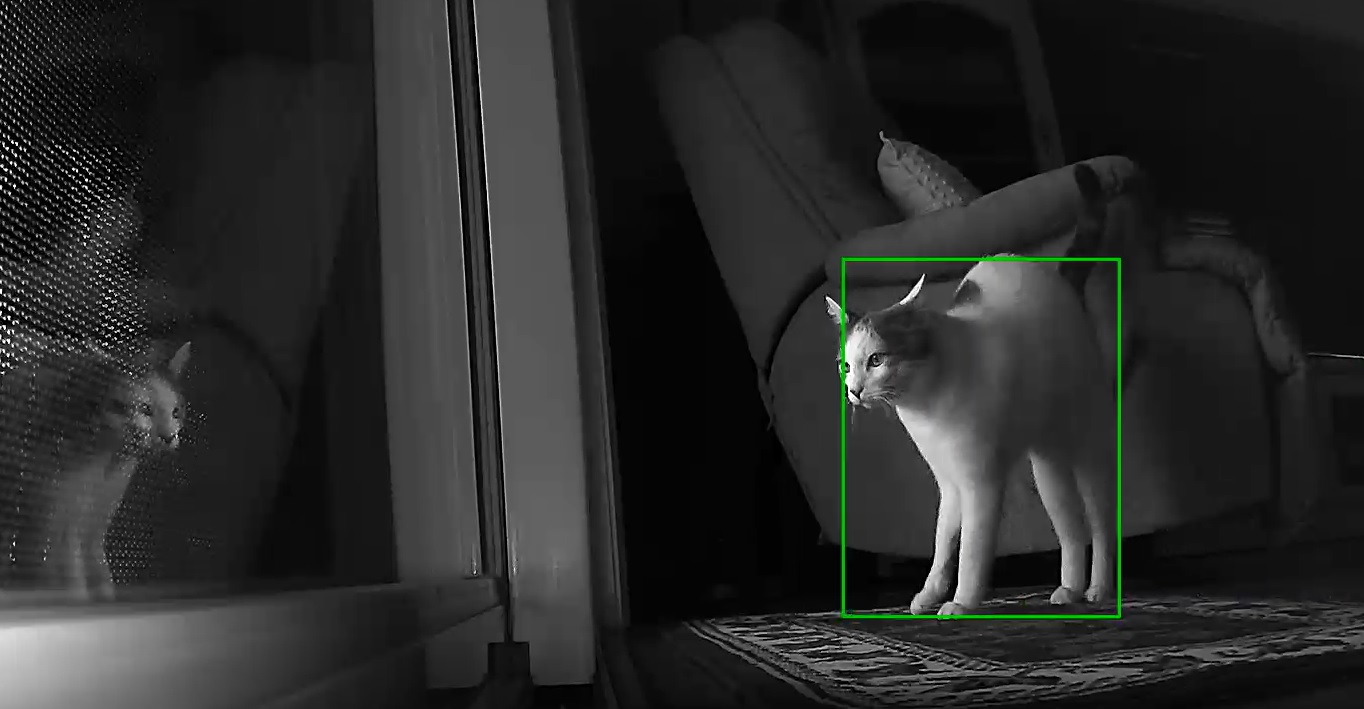

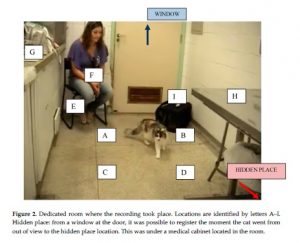

All cats also came to the veterinary hospital for a behavioral test. The cat’s carrier was placed on the floor of an exam room. Each cat was offered a bowl of food and was allowed to explore the room as they wished while their owner sat nearby quietly. The sessions were video recorded for later analysis of common signs of stress – such as tendency to hide, their body language, their activity levels and how much they meowed.

Results indicated no difference between the cortisol levels of sprayers with their matched control housemates (~500 ng/g). But both cats in each spraying dyad had higher levels of cortisol in their poop compared to latriners and their housemates (who were also similar to one another; ~400 ng/g). There were few behavioral differences among the cats, the most notable difference being that the cats from spraying households were more active during the behavioral test.

This study is very interesting because it suggests that cats living with other cats may be affected by the presence or stress of those other cats. However, the cat who is spraying or latrining is not necessarily MORE stressed out than their housemates. Instead, they’re all stressed – and it could be the spraying behavior that is elevating the stress levels of other cats in the home!

So why do some cats express that stress as house soiling? This is a question that merits further exploration – it could be a personality trait, a coping mechanism, a genetically mediated behavior, or something else! From this research, we can determine that spraying is likely associated with higher levels of stress; and in fact, other studies of cats’ fecal cortisol levels (where cats did not exhibit house soiling) have suggested much lower levels in the range of ~200 ng/g. The relationship between latrining and stress is less clear, although latrining cats still had much higher cortisol levels compared to the cats in previous studies.

A few other important observations from this study: the spraying households had on average six cats, and latrining households averaged 4.6 cats, suggesting that the number of cats in the home may directly contribute to both stress and spraying behavior. Previous studies have not found that cats in multicat households necessarily have higher stress levels than single cat homes. Access to the outdoors also did not seem to be a protective factor for spraying – most households with spraying gave their cats outdoor time.

This research does point to the importance of managing stress in households where spraying is present. Although we cannot determine if stress led to the spraying, or spraying is causing the stress, we can conclude that once spraying is present, stress is present, and a treatment plan is necessary. Treatment for spraying often includes increasing resources and distributing them throughout the home, addressing relationship issues between cats, increasing mental stimulation and play and promoting safety and choice for cats. My professional experience has been that many sprayers also benefit from anti-anxiety medication – and perhaps future research could explore whether or not placing a sprayer on anti-anxiety medication can reduce the fecal cortisol of both the sprayers and their housemates!

References

Ramos, D., Reche-Junior, A., Luzia Fragoso, P., Palme, R., Handa, P., Chelini, M. O., & Simon Mills, D. (2020). A Case-Controlled Comparison of Behavioural Arousal Levels in Urine Spraying and Latrining Cats. Animals, 10(1), 117.

Ramos, D., Reche-Junior, A., Fragoso, P. L., Palme, R., Yanasse, N. K., Gouvêa, V. R., … & Mills, D. S. (2013). Are cats (Felis catus) from multi-cat households more stressed? Evidence from assessment of fecal glucocorticoid metabolite analysis. Physiology & behavior, 122, 72-75.

Schatz, S., & Palme, R. (2001). Measurement of faecal cortisol metabolites in cats and dogs: a non-invasive method for evaluating adrenocortical function. Veterinary research communications, 25(4), 271-287.