My latest article about the science behind what it means to be a cat person…check it out over on the Dodo! or read on below!!

Humans love to categorize. As soon as a baby is born, our first question is often whether the baby is a boy or a girl. Are you a night owl or a lark? Are you a Republican or a Democrat? Are you straight or gay? What astrological sign are you? Do you prefer paper or plastic?

From these categories, we believe that we can infer other information about someone, a sort of cognitive shortcutting, so to speak. Of course, this shortcutting may lead to errors (and even prejudice), but in a world full of endless amounts of information, categorization can at least make things seem more manageable. How you categorize people may depend on your own interests and values. I know that when I meet someone, I kind of want to know if they consider themselves a dog or cat person.

What about you? Do you care if the people you are friends with are cat people too? What about a potential romantic partner? Dating sites even let you filter choices based on pet preference, and there are multiple website for meeting like-minded pet-loving singles such as Purrsonals.com and DogLoversPersonals.com.

Maybe, like me, you know that you consider yourself a cat person. But have you thought about how being a cat person might make you different from other people? Nowadays, the public tends to tag cat people as female (although that stereotype may be slowly changing), as being overly obsessed about our cats (hmmm, maybe true) and the word “crazy” is often attached to “cat lady.” And we are often described in comparison to …of course…”dog people.”

So what does the science say about us? Are we quantitatively or qualitatively different from non-cat people? Are our interactions with our cats somehow unlike the interactions people have with dogs? Are we female,obsessed and crazy? Let’s take a closer look at what the research to date has shown us.

Where are we?

First of all, a review of the scientific literature indicates that we are fewer in number than dog people (or at least we are harder to track down for the purposes of research), so we tend to be underrepresented in most research of the human-pet relationship. For example, a large study by Samuel Gosling and colleagues, looking at personality traits and identification as a cat person or a dog person found that only 11.5% of those who participated said they were a cat person (compared to over 45% identifying as a dog person). Another study of childhood attitudes toward pets showed that fewer subjects loved cats than those who loved dogs, and more people who are considering getting a pet are thinking of adopting a dog than a cat.

Is there a “cat person” personality?

Much of the psychological literature about personality revolves around a theory called the Five-Factor Model. It posits that there are five main facets to human personality(Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness and Neuroticism). Gosling’s study found that in comparison with dog people, we cat folk tend to be less cooperative and compassionate (Agreeableness), less outgoing and positive (Extraversion) and less self-disciplined and organized (Conscientiousness). We also tend to be more anxious and angry (Neuroticism) and more artistic and intellectually curious (Openness).

While that may seem like a mixed bag, the news doesn’t get better. Cat people also score themselves as less masculine and independent in comparison to dog owners; females are more likely to identify as cat people than men are, and more people indicate a dislike for cats than dogs. Another study found that cat people are more hostile and that they rate their own cats as more hostile, less friendly and less submissive in comparison to dog owners and their pets.

Are we really like our preferred pet type or is this all in our minds? The evidence is still unclear. One study found that while dog owners may experience their relationship with their dogs as a mirror (giving back acceptance and affirmation), we relate to cats with more of what is called a twinship — where we believe that our cats experience the same emotional states as us and are in tune with our emotions. If we buy these results, you could interpret this as dog people seek a pet who complements their personality, but that cat people like cats because they are more of a match to their personality. So next time you even think of calling your cat a “jerk,” “lazy,” or “stubborn,” take a hard look in that mirror.

Do cats give us toxoplasmosis and make us crazy?

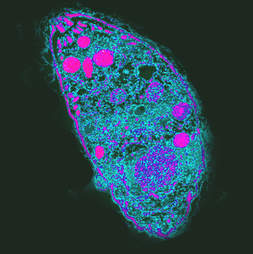

Toxoplasmosis is a disease caused by a parasite that can only reproduce in the feline digestive system. Without cats, there would be no toxoplasmosis, but it can hang out in several mammal and bird species.

It may have an effect on the dopamine system, often described as the reward center of the brain. Toxoplasmosis reduces the fear of cats in rats, and it slightly increases the attractiveness of cat urine smell to men. Current estimates for toxoplasmosis presence in the human population suggest that one out of three human is a carrier.

Those who are infected tend to be more extroverted (which contradicts most finding about “cat people”), and there may be some relationship between toxoplasmosis and suicide, self-harming behaviors, and schizophrenia.

Unfortunately, these findings led to an outrageous media outburst of unwarranted accusations that cats make us crazy, and that cats are using this parasite to manipulate our minds. I hate to burst the cat-hating media bubble, but I have to. An increased liking for the smell of cat urine does not prove that cats are the main cause of toxoplasmosis. While cat feces may contaminate water or food sources and make cats a major source of toxoplasmosis, direct contact with cats is not what spreads it: no study to date has found a definitive link between cat ownership and toxoplasmosis. The biggest threat? Eating and handling undercooked meat.

Are we less happy and healthy than dog people?

Contrary to popular belief, pet ownership doesn’t seem to reduce loneliness or depression,anxiety or anger, regardless of pet type, although the benefits of pet ownership may be dependent on your extended network of social support. People who own pets may be happier to begin with, not because they acquired pets.

Pet ownership reportedly reduces the risk of heart disease, and improves sleep and general health, but do these beneficial effects depend on whether you have a cat or a dog? Most of the studies demonstrating that petting animals lowers blood pressure used dogs, so we need more data on physical interactions between humans and cats. Dog ownership increases physical activity, but living with cat may have protective effects against allergies and asthma.

I think we can safely conclude that even if loving cats has no obvious immediate mental or physical health benefits, it is likely to do no harm. In fact, people are almost eight times as likely to be injured by their dog than their cat (think dog bites and tripping hazards), so maybe cat people do have a health advantage!

How much do we love our cats?

In general, we score lower on attachment and affection measures than dog owners. Is this because we really have a lesser relationship or are the scales flawed? For example, some of the questions on surveys measuring pet attachment may be biased. Questions like, “Does your pet pay attention and obey you quickly?,” “How often do you travel with your companion animal?,” and “Does your pet help you to be more physically active?,” may be aimed more at dog owners than cat owners (maybe we need questions/statements like “I let my pet sit on the dinner table while I eat” or “My pet helps me work on the computer”). Measuring our love for our pets is tricky, and the answers may depend on what questions you ask.

Research from the 1990s found that cat owners were less likely to consider cats as part of the family, although a more recent survey suggests that this sentiment is changing. In general, people report getting more social support from their dogs than cats. At the same time, people claim to have more negative interactions with their dogs than cats, so perhaps the expectations for affection that dog owners have can lead to greater frustration or disappointment in their pets.

Our attachment to our cats may depend on who else we live with. One study found that living with humans and cats lowers attachment to cats, but the more cats we have, the more attached to them we are. Perhaps having multiple cats decreases the likelihood of having a partner or roommate? Does the lack of a partner or roommate increase our desire to have many cats and to rely on them for social support?

And, not surprisingly, our attachment to our cats may depend on our individual cat and how we interact with them. An indoor-only lifestyle increases the time cats spend interacting with their humans, and in general, cats prefer to call the shots when it comes to human-cat interactions. When cats initiate contact, the interactions tend to be longer than when human approaches the cat, but cats may also be more willing to comply with interactions with women than men. Older cat owners tend to be more tolerant of a cat’s independent nature than younger folks, who prefer more “conformity” and less independence in cats.

Although complex and perhaps different from our relationships with dogs, it’s safe to say that people are attached to their cats. How we define and measure this attachment is an area begging for more research.

What do we think about cats?

A colleague and I recently conducted a study on pet person type and attachment to pets, and we allowed people to make open-ended comments at the end of the survey. We ended up not including these comments in the manuscript, but we found a few interesting trends. Cat people were more likely to anthropomorphize and emphasize their pet’s individuality with comments like “My cat is the smartest.” Dog people, on the other hand, were more likely to emphasize their pet’s obedience and make more general comments about dogs, such as “I love dogs” or “dogs are sweet.”

People also tend to have more extreme feelings about cats, either loving or hating them. We see cats as more independent, but are they truly aloof, or do we raise cats differently because of that belief? We believe cats have personality, but we also seem to think that a cat’s personality is at least in part dependent on their coat color. Perhaps our feelings about cats as a society would best be described as “slightly confused” and “mesmerized by YouTube videos.”

So what makes us a cat or dog person in the first place?

That is the million-dollar question. Is it experience? Do we happen to like cats because that is what our parents liked (in my case,no…I had to fight tooth and nail to get my allergic mother to let me have cats)? Is our affiliation affected by negative experiences with an animal as a child? (As someone who was bitten by both cats and dogs as a child, I can say again, for me, no). Does our personality steer us toward one type of pet or another? And can this identification change over the lifespan?

What does it all mean?

Even though science may have done a fair amount of exploration on what defines and describes the relationship between us and our cats, and what makes us cat people in the first place, we are still left with way more questions than answers! Hopefully, this will inspire many researchers to continue examining just what our relationship with our cats says about us. As someone who lives by science, I think the study of human-animal interactions is a hugely important and growing field. But at the end of the day, what being a cat person means to me is snuggling with my purring cat, and sometimes, that’s enough.

Absolutely loved your article! I personally am a dog person, and I’ve always been intrigued as to why I am so. As a psychologist, I’ve probably spent more than the average person thinking about why I love [my] dogs so much. I do love cats, too, but my affinity for dogs definitely runs deep.

One thing I wanted to share with you is that I’ve always thought that the nature of dogs attract certain kinds of people. As you know, most dogs are generally regarded as less independent than cats, perhaps be more willing to please, and are more apt to “following orders”, so to speak. Cats on the other hand, are oftentimes stereotyped as more aloof, independent, and appear to march to the beat of their own drum most of the time. All that being said, I always thought that perhaps people who experience a lack of control in their lives – whether conscious or unconsciously – may gravitate towards dogs because they essentially have a greater sense of control in the human-pet relationship. Those who are naturally more independent and who may be more self-assured prefer cats, because (like you said) they mirror their pets and their feelings are not easily thwarted if their feline friend refuses to give them attention or ignores them on any given day. What do you think?

Any way, great article. Definitely loved it. Thank you for sharing!

Paula,

I think you have so many great thoughts/questions that would make a great study (or several!). Just how to assess peoples’ pet preferences and emotional experiences/styles and need for control would be fascinating. I personally have never seen cats as aloof in general – and I think that when cats are friendly, people tend to say they are “dog-like,” but I would argue that many cats are just lovely! I think the big difference is the level of domestication and dogs just have cats beat on that one. I personally think that we can make up for their lack of domestication when cats are well-socialized, but most cats are severely undersocialized and their potential as pets is unrecognized. Thank you so much for reading and sharing your thoughts!